Samuel M. Stout’s journal kept in 1851 details his wagon train’s progress along the Oregon Trail. FWWM archives.

Each year, thousands of pioneers braved the Oregon Trail, which ran from Independence, Missouri, through Kansas, Nebraska, Wyoming, Montana, Idaho, and ended in either Oregon or further west to California. Emigrants needed to start their westward journey by mid-April to reach Oregon by October before grasses that fed livestock died, and mountain passes were covered in snow. The journey took around five months, with wagon trains only averaging 12-15 miles per day.

Journals written during or after the journey document what it was really like to travel those 2,000 arduous miles. Samuel M. Stout (1814-1877) was the captain of a wagon train headed for Oregon. Little is known about his life. His family moved from Kentucky to Indiana, and he later lived in Yreka, California, and Pierce City, Idaho. He was a wanderer, and there is no record that he had ever married or had children.

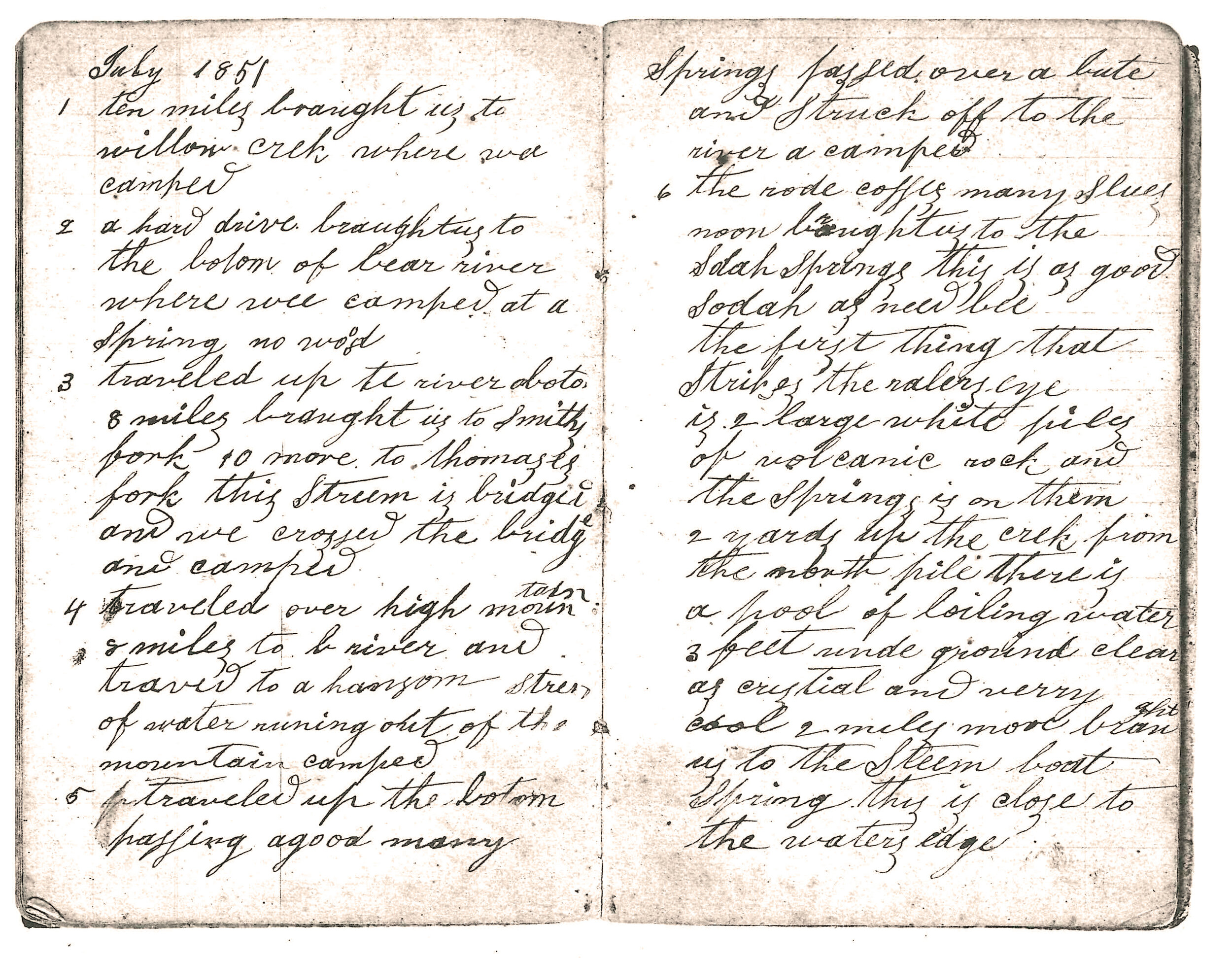

His sister, Nancy Stout Stott, along with her husband and four children, were also on the wagon train. She was pregnant at the start of the trip. From April 24 through September 2, 1851, Stout documented the wagon train’s journey in a small notebook. He recorded the month and each day’s activities, sometimes noting where they stopped or how many miles they traveled. Most entries are written in ink, though he switches to pencil at times. Some entries are difficult to decipher, from worn pages, smudged ink, faded marks, or indecipherable spelling.

They started in Independence, Missouri, on April 24, traveled six miles, then camped for five days. It snowed on the 29th, the day before their long journey began. By May 7, they had reached the west side of the Blue River near Rock Creek, Kansas. Here the train organized and named Samuel Stout as captain, Johnson May as lieutenant, and Nelson Miller as clerk. On May 10, the train camped after a rough and hilly ride through Wyeth Creek. Here Nancy Stout Stott gave birth to a son, Hezekiah. The next day the rain was coming down too hard to continue, so they stopped, and the men hunted. Over the next few days, they passed through sandy hills and met two other trains on the trail.

Hezekiah Stott (left) was born on May 10, 1851, on a wagon train heading to Oregon. In the right-hand photo, Mary Ann Stott Cornwell (left) and their mother, Nancy Stout Stott (center), were both on the wagon train. Emma Stott (right) was born later. FWWM archives.

On May 18, the train passed Fort Kearny in Nebraska, around 330 miles west along the trail. It was built in 1848 to protect emigrant trains. On May 21, the cattle took fright and broke free. Most were found eight miles away, but the crew spent the whole next day looking for the rest of them. On May 26, the train missed the crossing over the Platte River. They met soldiers with news of hostile Indian people, then traveled with a herd of buffalo. The next day, 30 cattle broke free. On May 28, the cattle again broke free at 3:00 am. By 7:00 am, all were recovered, and the train set out at its usual time. Later that night, the cattle again spooked and escaped but were quickly returned and yoked and tied together.

On May 29, Stout wrote: “In the morning we came near some Indian wig wams and lots of Sioux. This is their nation. 4 [o’clock] we met a party of them on their [ponies]. . .” It is the first mention of the party encountering Indian people along the trail. On May 31, the train passed 28 wagons loaded with goods. At 3:00 pm they first saw in the distance Chimney Rock, a prominent landmark along the trail around 580 miles from Independence. On June 6, they reached Fort Laramie, Wyoming, an important resupply point 656 miles from the start. Stout recorded that there were many Indian people in the area.

Throughout June, Stout’s train traveled through sandy hills, creeks, and bluffs. They hunted buffalo and small game and saw the Sweetwater Mountains in the distance. Some of the oxen pulling the wagons became ill from drinking alkaline water. On June 25, they stopped to rearrange the loads in their wagons. Later, a train of mules came upon them. One of the mules kicked a yoked ox, starting the team and sending three teams running. Despite this, Stout wrote, “no harm done. We drove all nite. The road good, 1 hill.”

For the next few days, the team hit patches of good grazing grass and a few good springs of water, but there was no timber. At Soda Springs, Stout notes the change in the landscape to volcanic rock. On July 8, many cattle again developed alkali sickness. On July 11, they reached Fort Hall, Idaho, around 1,150 miles from the start of the trail. This location marks where the Oregon and California Trails diverge. At this point in the journey, Stout switched from writing in ink to pencil, which is much more difficult to read.

On July 15, they lost the first member of their party. Per Stout: “this morning there was a child died, a little boy 3 years old S. McCoy we carried the remains to the big marsh. Here we [buried] it.” The rest of July was a mix of easy and hard traveling. They went many miles without ready grass or water, and the roads were steep and rocky in places. On July 31, they camped at a creek with another wagon train led by Joseph Williams. On August 3, Stout begins writing in pen, which is more legible. “We started but Mr. Houlett was too sick to travel. Advanced one mile and camped.” On August 4, Houlett insisted the train continue, but by night his condition had worsened. That same day, Joseph Williams’ train buried P. Black, who succumbed to wounds received during a skirmish with Indian people at Rock Creek. By August 5, Houlett was dead from “good mortification,” which could have referred to necrosis or gangrene.

On August 13, Stout reports that “the past two days hundreds of Cayuse Indians passed us [fleeing] from the [danger?] that had killed some of them.” It is uncertain what he was referring to. On August 17, Stout recorded “2 miles down to camp while resting in the shade Mrs. McCoy took a coal of fire in her wagon and blew it up burning 7 ½ lbs powder but did not hurt her and child very bad.” This family shares the surname of the child who passed away in July and may be his mother and sibling. By August 25, they arrived at the Deschutes River Crossing, just east of The Dalles in Oregon. The cost to ferry the train across the river was $5 per wagon.

On the other side, the terrain was steep. They stopped to camp, unable to find a water source for their cattle. August 30 brought them to Barlow Gate. Stout writes, “here wee make the cascade mountains. Here wee lost all distance of hours after the rain commenced. The rode ruff without much grass.” Stout’s journal ends mid-sentence on September 2: “T. Denney met us with 3 yoke oxen today. We passed the swamps and camped at the . . .”

By this point, the train was on the last leg of the journey, taking the Barlow Road across the south shoulder of Mount Hood. It was a steep climb to the Barlow Pass before descending into the Willamette Valley toward Oregon City. The train eventually made it, and Nancy Stout Stott’s family settled in Portland, Oregon. James M. Cornwell arrived in Oregon in 1852. He married Mary A. Stott, Samuel Stout’s sister-in-law. In 1861 they settled in the Walla Walla Valley. This journal was donated to the Museum by his descendant, Olive Cornwell Osborne, in 1970.

Samuel M. Stout is buried in Crescent Grove Cemetery in Tigard, Oregon. While much about his life is unknown, his words are preserved in the diary he kept on one of his many journeys across the Oregon Trail.